on incompetence and malice

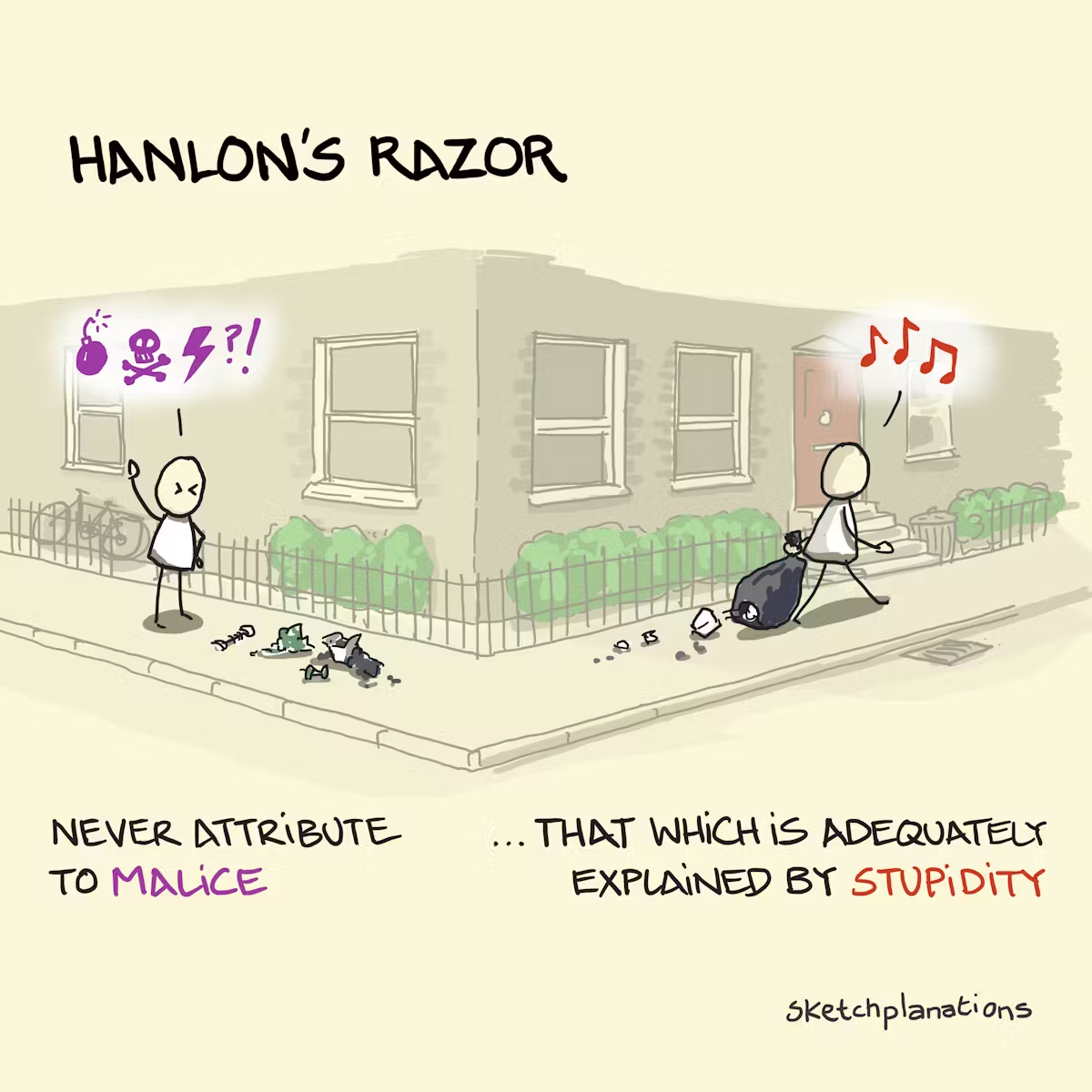

Hanlon's razor states:

Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.

This popular adage focuses on the recipient of said stupidity. How many of us have felt that an impersonal bureaucracy is somehow working against us personally? Or that a friend meant to slight us, when perhaps they simply forgot to think about their actions? Or that a coworker or boss is intentionally ignoring us, when in reality they're just trapped in a busywork cycle of their own making?

Inverting Hanlon's razor, you get Grey's law:

Any sufficiently advanced incompetence is indistinguishable from malice.

Here we focus on the situation in an impersonal context. You could equally imagine a human observer or AI agent evaluating the situation, struggling to distinguish two patterns of behaviour that have striking similarities in their externally observable effects. It brings to mind epic fiascos such as the COVID vaccine rollout in California or Boeing 737 MAX or the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident - each highlighting failure modes of large-scale systems and incentive structures.

For better or worse, "sufficiently advanced" is often best read as shorthand for big, complex systems where the left hand and the right hand are blissfully unaware of each other. (Though the Peter principle means it can apply to individuals as well, at least when they are given more power than they have skill to wield.)

In that spirit, I propose a corollary to both Hanlon's razor and Grey's law:

When you are incompetent, others will see it as malice.

When you neglect to include the right people in a discussion, or change plans with little or no notice, or forget about a longstanding tiff between two people you just added to the same group, or take on too much and have to back out of it, or speak without thinking - eventually someone will mistake your incompetence for malice.

This can be frightening, but I prefer to think of it as a twofold reminder.

First - a few key organizational habits significantly reduce your potential "incompetence surface" (by analogy with attack surfaces in cybersecurity):

- keep slack in your schedule, and start saying no before you reach 100% capacity

- double-check your calendar before booking things

- maintain a task list somehow: if you accept a task, it goes on the list

- communicate! when you plan an event, give multiple reminders; if you need to change plans, let people know as soon as possible

I definitely am not 100% successful at following these habits - the only people I know who are intrinsically enjoy organization. Which absolutely is a personality type that exists! It's not my personality type, but that's OK. This is an area where some effort really is better than none: 70-80% success is more than enough to impress most people.

(Plus these habits become more and more automatic over time. Accept a task? Goes on the list, right away, before you have time to forget. Scheduling with someone? First step: check my own calendar, make sure there's no overlap.)

Second - no matter what you do, no matter how diligent you are, you will make a mistake at some point that someone will interpret as malice. We are all incompetent sometimes, even at things we're normally competent at. This is part of being human, and it is especially part of taking responsibility for any person, team, organization, process, project, or product. Don't let fear of this reaction stop you from making clear decisions on imperfect knowledge!

That said, don't let your prior decisions railroad your future actions. If a decision was wrong, acknowledge that, work to fix it, and move on.

And: even if you are a highly trained and competent professional, you will have off days. Maybe you're a new parent, with all the sleep deprivation that entails. Maybe you catch that nasty cold that's been going around, the one with the 3-week lingering cough and vile globs of mucous everywhere. Maybe you get bad news in some completely unrelated area of your life, and need time to process it. That's OK. No one expects you to be on 100% of the time - and as we accept more vulnerability in leadership, it can be valuable to just admit your limitations sometimes.

(For what it's worth: as someone who likes to think he's smart, driven, and capable, I find this last bit hard. It's one of the leadership skills I'm looking to work on in 2025.)